I’d like to say I grew up on text adventure games, even though that would identify me as olde, but in reality the genre was already well-developed when I was in my teens. Still, I fondly recall getting nearly all of the Infocom games for my Commodore 64, during the period between 1984 and 1988. By 1989 the market had shifted, Infocom was making games with actual graphics and the text adventure pretty much died. It would be many years before freely-available interpreters and languages for writing text adventures would lead to a minor renaissance of the genre.

You can find information about a lot of the resultant games and more at The Interactive Fiction Archive.

Information on Infocom games can be found at Infocom – The Master Storytellers (and, of course, Wikipedia).

A text adventure was simple to learn–type your actions at a command prompt, read the results, repeat until you have solved all the puzzles in the game–but often the biggest puzzle was figuring out which words or commands the game could understand and the proper way to present them.

Back in that mid-80s era when computer graphics were less sophisticated (ie, crude, terrible) I spent many hours working through Infocom’s games. This was also my first bit of co-op gaming as I usually had a friend assisting me. Two brains will theoretically solve puzzles more capably than one. Until both brains get completely stuck, that is. That’s when you mail order the Invisiclues hint book and wait weeks to finally get an answer. It was the gaming equivalent of walking to school uphill in the snow both ways. And we liked it!

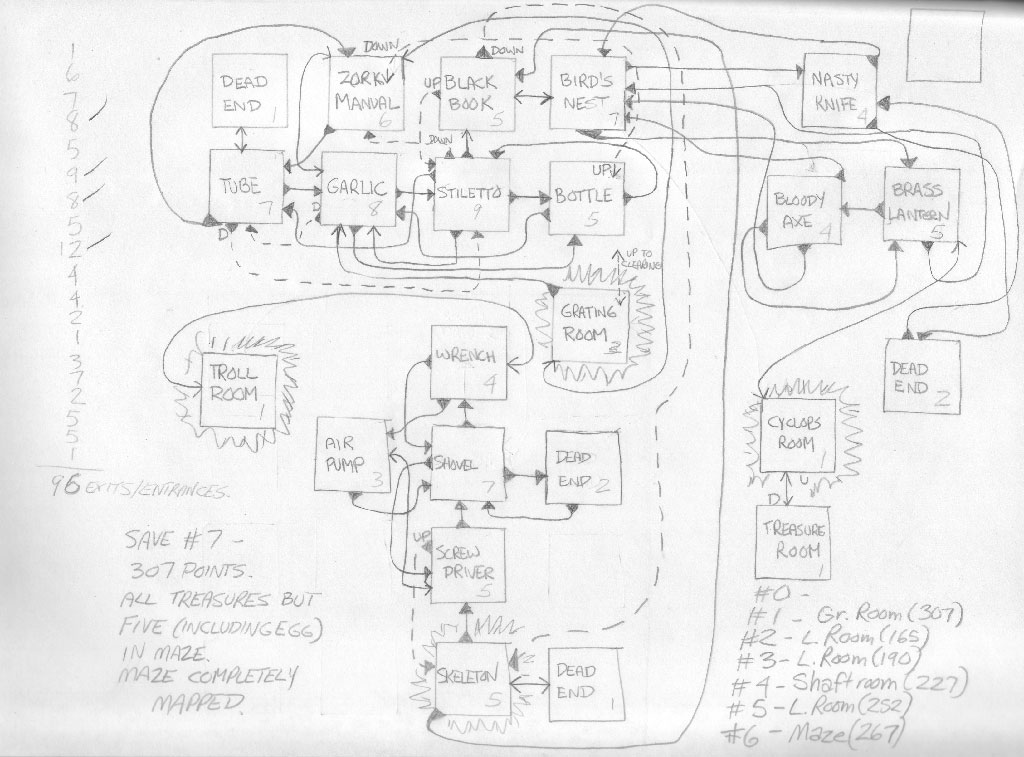

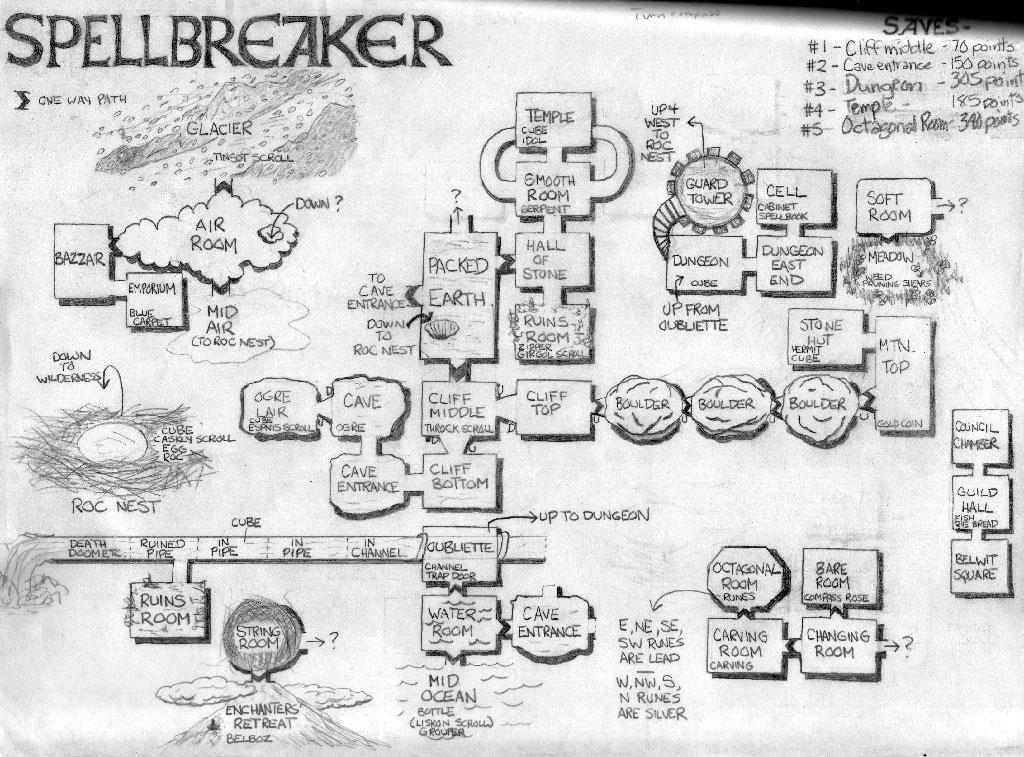

One of the key requirements of playing an Infocom game was making a map. Sure, you could try memorizing the game world and with some simpler titles it might even work, but making a map was essential for nearly all Infocom games. I’m fairly certain that utter madness was the only reward for successfully mapping out all of Zork I and its mazes.

I took to making most of my maps in a sketchbook and recently scanned in some of the more detailed maps. By the end I think I was playing the games more to make the maps than to play the actual games. Going back and looking through the maps also made me realize there are more than a few of these games that I left unfinished. Now they taunt me and I consider re-playing them using programs like Gargoyle or Windows Frotz to help make the experience more pleasurable than those halcyon days of yore with my Commodore 64 displaying 40 whole characters of text on a single line. 40! And I always knew I had successfully solved a puzzle because the 1541 disk drive would start grinding away madly to fetch a new chunk of game. Today I can use Trizbort to automate the mapping process entirely but I know if I do go back I’ll have that sketchbook at hand and start doodling again because it was part of the magic.

And a game without magic is just a game.

Here are the maps I’ve scanned so far.

First up is Zork I. The maze in this game (twisty passages, all alike) requires you to drop items in order to successfully map it out. Following all of these lines still gives me a headache. I never finished the game but I did finish the maze!

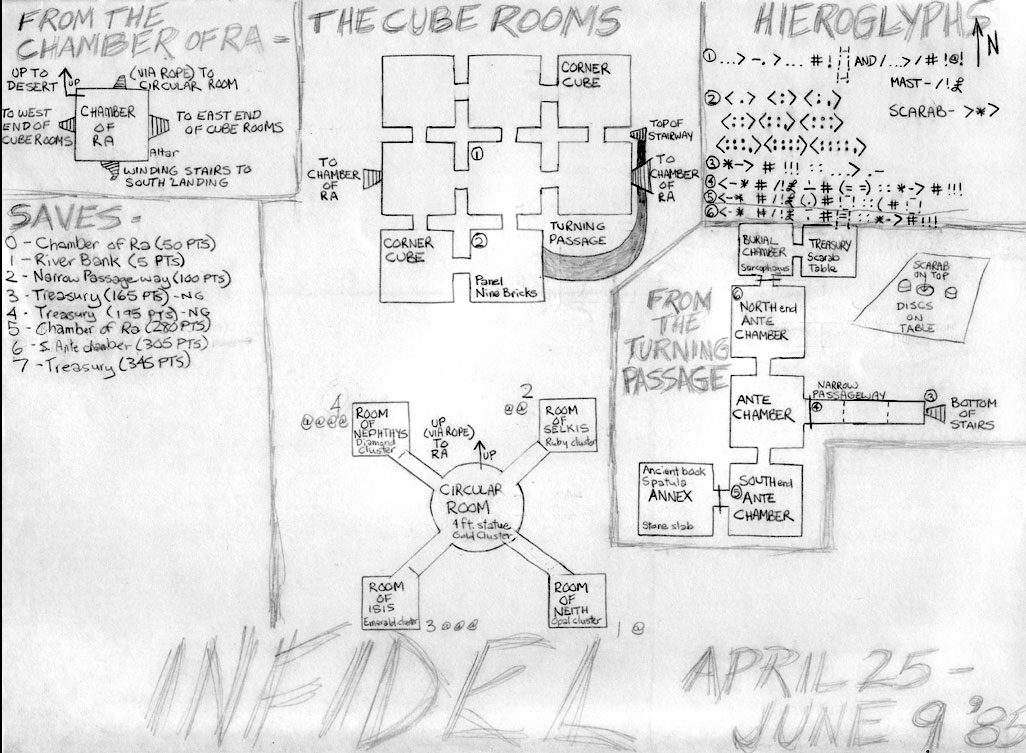

Next is Infidel, featuring ASCII hieroglyphics and even a start and end date for the game playthrough. How nerdy.

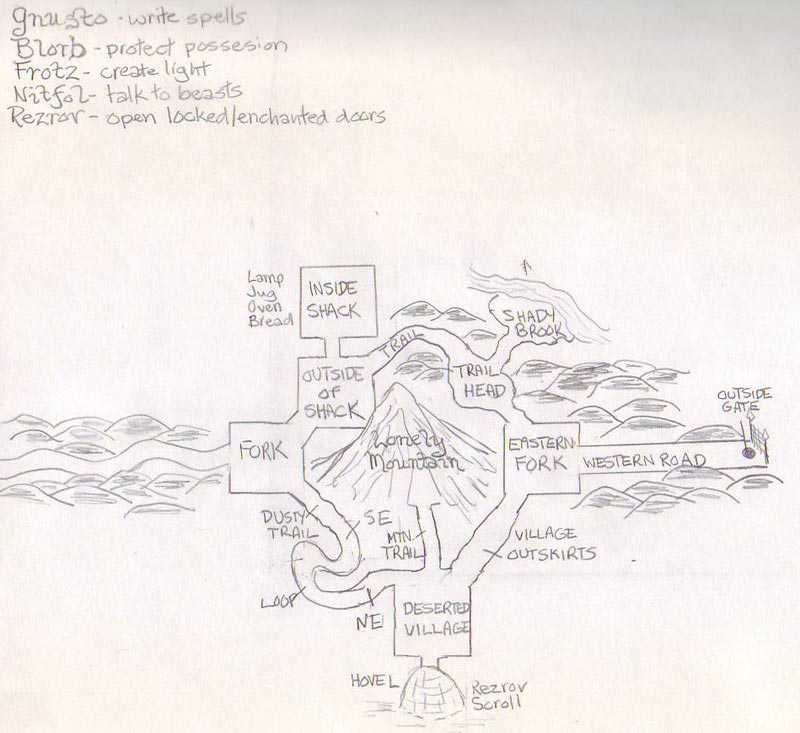

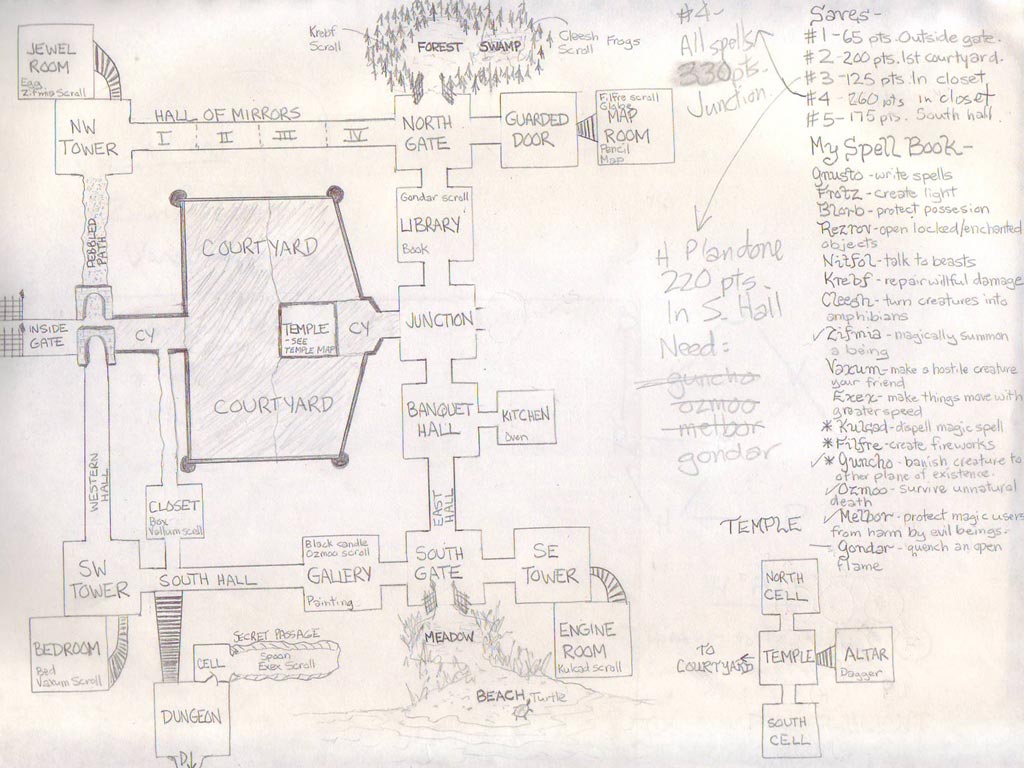

I have two Enchanter maps, the first image being from the start of the game and the second being the next area. I like the turtle.

And the follow-up area:

Finally the maps for Spellbreaker even includes 3D shading. Fancy!